I enjoyed this morning's discussion on Radio 4's 'Start the week' – check the link for iPlayer listening.

The participants were Richard Holloway, once a Scottish Bishop, Karen Armstrong, the former nun and writer on religion, and Jonathan Safran Foer, the Jewish writer whose book inspired 'Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind'.

At one level it posed some big questions for traditions like Quakerism where religious meetings seem to be devoid of almost everything except silence. Even though both Armstrong and Holloway would describe themselves as 'Christian agnostics', both agreed about the importance of regular ritual and religious observance.

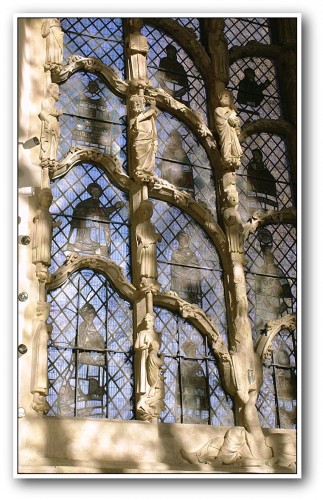

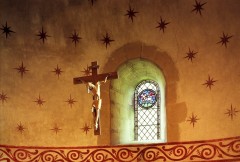

Holloway is a churchgoer in a place which sounded quite 'high'. He did not want the centrality of Christ's message to be lost, for its immense contribution to the attitudes and behaviour of people from a Christian faith. He believes in the mystery of the universe as a totality, but not in a God that is separate to it.

He does not feel that any one religion has a formula that explains that mystery.

Armstrong speaks at the Royal Literary Society in March and argues that religion has more to do with behaviour than belief, and urges us to make compassion ‘a clear, luminous and dynamic force in our polarised world’.

Jonathan Safran Foer celebrated the questioning spirit of Judaism - where no matter of faith was closed to inquiry. He has brought out a book celebrating the complex and obscure ritual of Passover, which is the single greatest enduring legacy of their faith in the lives of a quarter of a million New York people of Jewish birth.

All agreed about the centrality of regular gatherings of people who would otherwise be strangers in a common spirit of devotion and celebration. These should be meetings of those who do not put dogma above practice: 'the Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath'. The message seemed to be 'if you are not part of a community like this, start one!'

There was a challenge to contemporary Islam to show it was able to welcome strangers in this non-dogmatic spirit, and implicitly another to the supposed reality of virtual computer worlds of all kinds.

In a different way this weekend I noticed a similar challenge in a recorded symposium at UCL on 'Beefcake: gay men and the body beautiful':

The editor of Attitude demands that gay men throw away their online networking tools Grindr and Gaydar and simply get together. The influential Mark Simpson who endlessly trumpets his invention of metrosexual man, seemed completely indifferent. And in last night's 'Room 101' Carol Voordeman got the biggest applause when she said the 800m users of Facebook should simply stop using it...

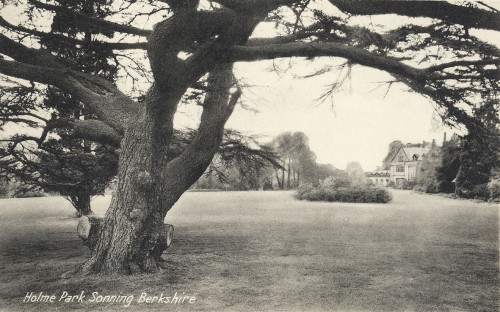

The beech is the tree of the Chilterns. Massed on the hilltops, they create great cathedrals of trunks and reaching branches, beneath a dense covering of dry leaves. This tree on Swyncombe Down is one of a

The beech is the tree of the Chilterns. Massed on the hilltops, they create great cathedrals of trunks and reaching branches, beneath a dense covering of dry leaves. This tree on Swyncombe Down is one of a