An acquaintance (whose accent locates him in the mid-atlantic, but whose prejudices are decidedly continental) once said to me that 'nothing of world class is ever produced by British artists'.

We were on the steps of the Royal Academy at the time. One collector who would certainly have disagreed was Paul Mellon (1907-99) the pick of whose Yale Center for British Art is on tour to the RA until January 27, 2008.

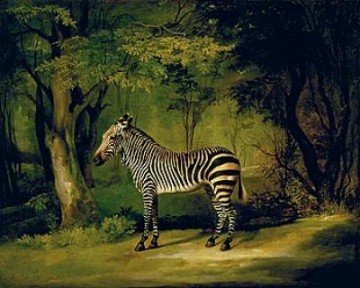

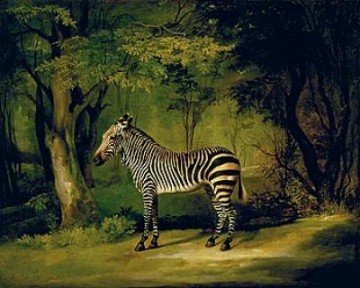

Mellon got his money from his father, the third richest man in America, and his taste for British art from spending his earliest days in England. Christened in St George's Chapel, Windsor and educated at Cambridge, he bought his first major painting, Stubbs' 'Zebra' in 1960 for £20,000. So unfashionable was painting of Stubbs' era that it was sold in a bric à brac sale by Harrods.

This astonishing portrait of 'the queen's she-ass' pictures it in a pool of golden light in a lush imagined forest. The creature, newly arrived at Queen Charlotte's menagerie from South Africa, has the look of a miraculous mythical beast. St Eustace might appear at any moment.

Mellon's collecting was intuitive. He mistrusted art historical analysis and bought because a picture appealed, not because its narrative impressed. In a decade or so he assembled (and subsequently gave away) a collection that is a roll call of the greats of British art: Hilliard, Hogarth, Reynolds, Gainsborough, Turner, Constable, Blake, Wright of Derby, Landseer, Palmer, Zoffany and Dadd. All are magnificently represented in the RA show. In addition there are superb topographical artists like Paul Sandby, caricaturists like Rowlandson and names new to me like John 'Warwick' Smith (1749-1831), John Robert Cozens (1752-97) and William Turner of Oxford (1789-1862) whose 'Donati's Comet' is a surreal night-time view almost reminiscent of Magritte.

The star of the show is Turner's vast, dazzling 'Dort Packet Boat' (1818), described then as 'one of the most magnificent paintings ever exhibited'. Turner's mastery of light is triumphant.

Two smaller Turners are almost as stunning. 'Staffa, Fingal's Cave' (1832) was completed the same year as Mendelssohn's work. A grubby little steamer pitches in a storm beneath the sunlit splendour of Staffa's cliffs.

In his 'Eruption of Vesuvius', minute figures are panic-stricken on the shore, powerless against the great red fury of the volcano.

In his 'Eruption of Vesuvius', minute figures are panic-stricken on the shore, powerless against the great red fury of the volcano.

Constable's 'Hadleigh Castle' (1829) is another blockbuster. From not very close up at all the 6 foot wide painting disintegrates into fractured, glittering brushwork. Constable's angry grief at his wife's death is painfully visible.

Mellon was not only a great collector of paintings – he was also one of the greatest book-collectors of the twentieth century. Works on show include Caxton's Canterbury Tales (perfect presswork, even at the very beginning of printing in England); the magnificent Kelmscott Press Works of Chaucer; and the only hand-coloured edition of Blake's gorgeous Jerusalem. In plate 99 an androgynous Jerusalem is clasped by Jehovah 'awaking into his bosom in the life of Immortality'.

Save for Burne Jones' collaboration with Morris, Mellon avoided artists associated with high Victorian excess. There's no sickly sentimentality here. Mellon's intuition was razor sharp - they may be unfashionable, but these are works of superb quality and refinement, in huge contrast to the masochistic indulgence of the Baselitzes on show on the floor below.

...there's an awful lot going on. Somebody should make a book about all the things to be found under London's 25 miles of railway arches. The arches are a natural home for wine vaults and fringe theatres. Dodgy car mechanics also thrive in the dark spaces beneath curving Victorian brick, but you can get much more than your car serviced under the arches in Vauxhall, where dubious saunas cosy up to brightly lit cafés and DIY specialists.

...there's an awful lot going on. Somebody should make a book about all the things to be found under London's 25 miles of railway arches. The arches are a natural home for wine vaults and fringe theatres. Dodgy car mechanics also thrive in the dark spaces beneath curving Victorian brick, but you can get much more than your car serviced under the arches in Vauxhall, where dubious saunas cosy up to brightly lit cafés and DIY specialists.  An art gallery called the

An art gallery called the

It's funny in a

It's funny in a

Hepworth picked up on it when she wrote "St Ives has absolutely enraptured me, not merely for its beauty, but the naturalness of life". She loved the sense of community as well as the:

Hepworth picked up on it when she wrote "St Ives has absolutely enraptured me, not merely for its beauty, but the naturalness of life". She loved the sense of community as well as the:

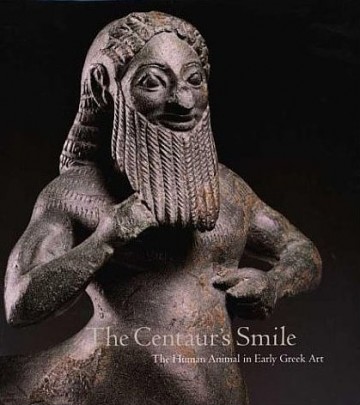

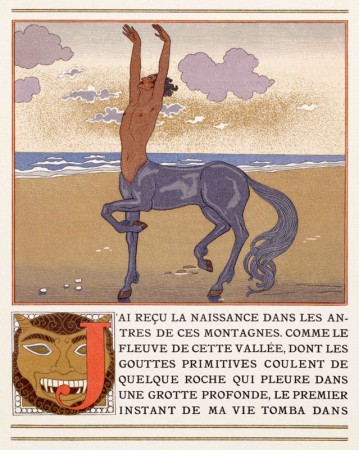

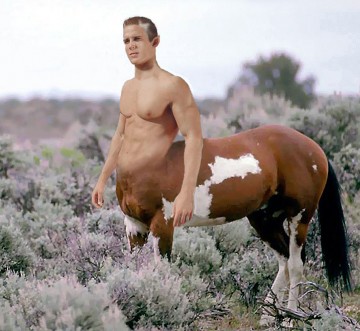

Other interesting editions of the de Guérin story include one printed by Ricketts and Shannon at the Vale Press in 1899 and this art deco interpretation featuring a distinctly un-menacing centaur by George Barbier (1928). Ricketts returned again and again to the centaur theme. In 1902 the artist and his long time collaborator Shannon were the models for a small painting of Nessus and his stolen bride Dejanira in which:

Other interesting editions of the de Guérin story include one printed by Ricketts and Shannon at the Vale Press in 1899 and this art deco interpretation featuring a distinctly un-menacing centaur by George Barbier (1928). Ricketts returned again and again to the centaur theme. In 1902 the artist and his long time collaborator Shannon were the models for a small painting of Nessus and his stolen bride Dejanira in which:

Which are the world's 50 greatest works of art? The Telegraph has published

Which are the world's 50 greatest works of art? The Telegraph has published

What is the 'real meaning' of art and what value should be placed on what is 'authentic' over the work of copyists?

What is the 'real meaning' of art and what value should be placed on what is 'authentic' over the work of copyists?

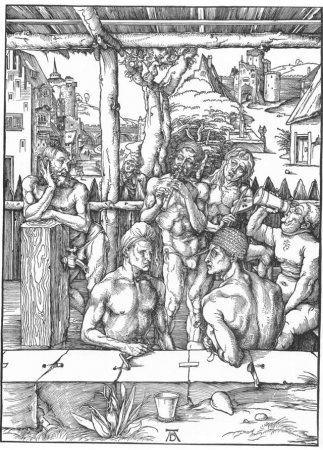

By Dürer's time the artist, not the subject, was the focus. His work – including a prominent monogram – was faithfully copied by a highly talented printmaker called Marcantonio Raimondi. In 1511 Dürer issued a devastating warning to anyone tempted to infringe what he was effectively asserting as his copyright: "Hold! You crafty ones, strangers to work, and pilferers of other men’s brains. Think not rashly to lay your thievish hands upon my works. Beware! Know you not that I have a grant from the most glorious Emperor Maximillian, that not one throughout the imperial dominion shall be allowed to print or sell fictitious imitations of these engravings? Listen! And bear in mind that if you do so, through spite or through covetousness, not only will your goods be confiscated, but your bodies also placed in mortal danger."

By Dürer's time the artist, not the subject, was the focus. His work – including a prominent monogram – was faithfully copied by a highly talented printmaker called Marcantonio Raimondi. In 1511 Dürer issued a devastating warning to anyone tempted to infringe what he was effectively asserting as his copyright: "Hold! You crafty ones, strangers to work, and pilferers of other men’s brains. Think not rashly to lay your thievish hands upon my works. Beware! Know you not that I have a grant from the most glorious Emperor Maximillian, that not one throughout the imperial dominion shall be allowed to print or sell fictitious imitations of these engravings? Listen! And bear in mind that if you do so, through spite or through covetousness, not only will your goods be confiscated, but your bodies also placed in mortal danger."

According to some '

According to some '

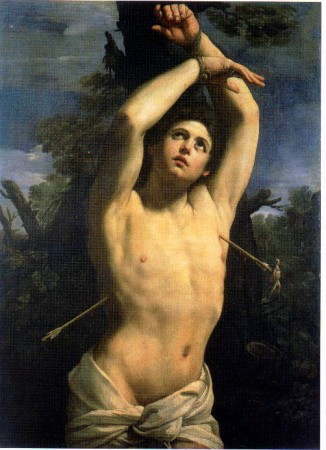

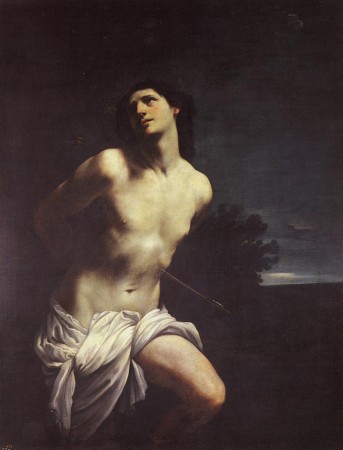

Seven paintings, all of the same subject: a beautiful, almost naked youth, tied to a tree, in the throes of martyrdom. Five are almost identical versions of the same composition, from galleries as far away as Puerto Rico and New Zealand. All are uncompromising in their directness. The painting from Genoa inspired Wilde, Mishima and Pierre & Gilles. Stendahl claimed they so distracted the faithful that they had to be removed from churches.

Seven paintings, all of the same subject: a beautiful, almost naked youth, tied to a tree, in the throes of martyrdom. Five are almost identical versions of the same composition, from galleries as far away as Puerto Rico and New Zealand. All are uncompromising in their directness. The painting from Genoa inspired Wilde, Mishima and Pierre & Gilles. Stendahl claimed they so distracted the faithful that they had to be removed from churches.

By 1864 Millais' style had evolved considerably. In 'Leisure Hours' (the quotation marks are the painter's) he has painted the Pender sisters as perfect ornaments, trapped in enforced idleness just as much as the goldfish in the bowl in front of them. The paintwork is a little looser and without distractions. The blank stares and suffocating stillness of the composition all add to the narrative, unlike some of his later portraits of women and children, which contrive to be either sickly sentimental or alienatingly haughty.

By 1864 Millais' style had evolved considerably. In 'Leisure Hours' (the quotation marks are the painter's) he has painted the Pender sisters as perfect ornaments, trapped in enforced idleness just as much as the goldfish in the bowl in front of them. The paintwork is a little looser and without distractions. The blank stares and suffocating stillness of the composition all add to the narrative, unlike some of his later portraits of women and children, which contrive to be either sickly sentimental or alienatingly haughty.

In his 'Eruption of Vesuvius', minute figures are panic-stricken on the shore, powerless against the great red fury of the volcano.

In his 'Eruption of Vesuvius', minute figures are panic-stricken on the shore, powerless against the great red fury of the volcano.