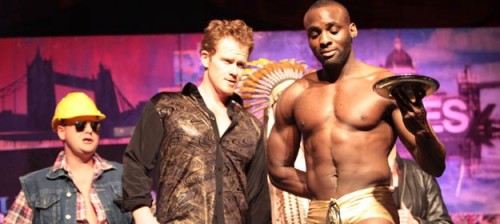

It's been an operatic sort of month. First a highly ritzy and very gay take on Mozart's Don Giovanni at the nightclub Heaven and then the pick of the crop at Garsington Opera's pre-opening show. And sandwiched in between, my own moment under the lights, lip-syncing incompetently along to scenes from pieces including the Marriage of Figaro for a very brief video insert into be show during the Garsington production.

To begin, the Don's trip to Heaven. First performed in 1787 with the subtitle 'the rake punished' Don Giovanni is ranked the seventh most popular opera in the world, with any number of productions running concurrently, each with their own light to shed on this sleazy tale of a sexually rapcious man-about-town.

A little gender-bending did the Don no harm at all. At Heaven all his conquests were male, and the set-piece catalogue aria chronicled his victories not around Europe but in the gay cruising grounds of London of the 1980s.

The lyrics by Ranjit Bolt were scatalogically hilarious, and economical too, what with the cuts that pared the opera down from almost 3 hours to 90 minutes:

Listen Eddie, I have drawn up this list here -

And I’m not talking merely the gist here -

Not a shag he has had has been missed here –

...Bankers, beggars, losers, winnners

All supply this prince of sinners

He has no time for the ladies

Takes the back door into Hades

Any size or shape of sha-ade

Indiscriminately laid!

He needs a lock

Put on his cock!

...People fall for this seducer

Just like fruit into a juicer

Those who call upon this lecher

Will be brought out on a stretcher

As the lead, the improbably named Australian Duncan Rock held the show together, with a powerful baritone voice shaped by his experience at ENO and Glyndebourne. His enviable physique was more than enough distraction for at least half of the grinning audience of around 400, which had to cope with poor acoustics and a slightly disorganised promenade performance. Also outstanding was Mark Dugdale as 'Zac'.

The orchestra of 10 were crisp and elegantly communicative. Even the Village People and Maggie herself put in a (distinctly dubious) appearance.

What then would all this have in common with a top flight production at Garsington Opera, in its second year at the Getty's Wormsley Park, just off the M40 near Watlington and what was your correspondent doing making a video for the show?

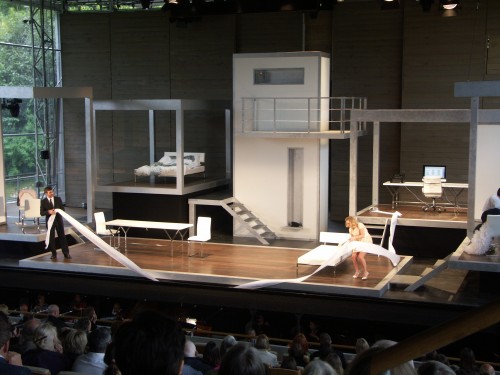

The trite answer is cocaine, since both shows featured enthusiastic use of the drug. With its achingly trendy set and snappy modern dress, Garsington's production is almost as far from 'straight' as was the Stephen Fry and Paul Gambaccini sponsored production at Heaven. Both feature imaginative takes on the catalogue aria, with a printer at Garsington spewing out an improbable 50' of conquests' names.

The auditorium at Wormsley is a wonderfully contemporary-looking semi-permanent structure by Snell Associates with completely clear sides and a back wall of exposed timber. It is set at the foot of the estate's home farm, close to a lake, and reached by a two and a half mile drive through private parkland.

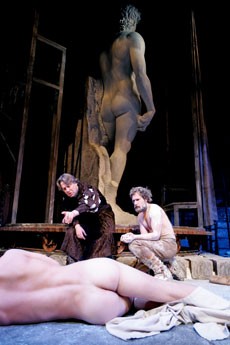

So just what were a bunch of amateurs doing contributing to this glittering evening? Thankfully little more than a couple of minutes of footage was shown on of us on a TV screen, as Don Givanni channel-hopped by iPad through opera videos, whilst waiting for his dinner.

The joke in the opera is that a snatch of Mozart's own Marriage of Figaro is played by the orchestra. The joke in the filming is that he catches glimpses of a series of extremely varied takes on opera production, from a creaky Dröttnignholm style full-wig 'Cosa Rara', to a completely deconstructed and very grimy 'regietheater' modern dress interpretation of the Marriage of Figaro, complete with vodka bottle, pills and porn magazine.

We got to work for a whole day with the full show's director, Daniel Slater and its designer, Leslie Travers, and they proved to be models of patience in spite of being confronted with complete amateurs. Several of my fellow cast members shone, and I lost count of the number of times I slid my hand up the thigh of my unfortunate victim, and had a gun thrust into my mouth by her jealous boyfriend. That particular moment thankfully ended up on the cutting room floor.

All three experiences proved the ability of outstanding art to withstand almost any treatment, and taken together they have made for a particularly memorable month.

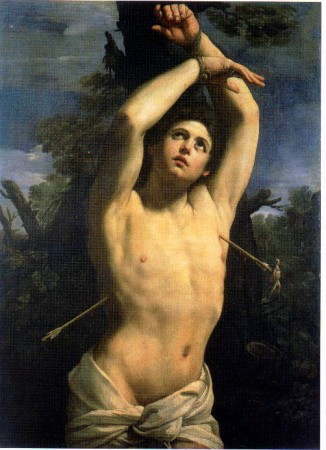

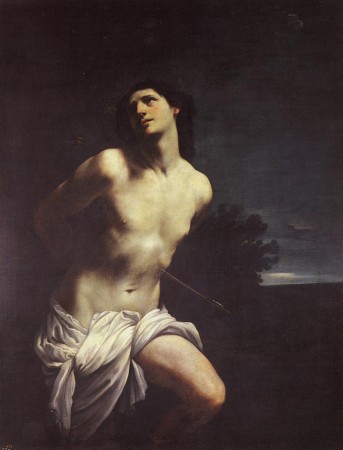

Seven paintings, all of the same subject: a beautiful, almost naked youth, tied to a tree, in the throes of martyrdom. Five are almost identical versions of the same composition, from galleries as far away as Puerto Rico and New Zealand. All are uncompromising in their directness. The painting from Genoa inspired Wilde, Mishima and Pierre & Gilles. Stendahl claimed they so distracted the faithful that they had to be removed from churches.

Seven paintings, all of the same subject: a beautiful, almost naked youth, tied to a tree, in the throes of martyrdom. Five are almost identical versions of the same composition, from galleries as far away as Puerto Rico and New Zealand. All are uncompromising in their directness. The painting from Genoa inspired Wilde, Mishima and Pierre & Gilles. Stendahl claimed they so distracted the faithful that they had to be removed from churches.

By 1864 Millais' style had evolved considerably. In 'Leisure Hours' (the quotation marks are the painter's) he has painted the Pender sisters as perfect ornaments, trapped in enforced idleness just as much as the goldfish in the bowl in front of them. The paintwork is a little looser and without distractions. The blank stares and suffocating stillness of the composition all add to the narrative, unlike some of his later portraits of women and children, which contrive to be either sickly sentimental or alienatingly haughty.

By 1864 Millais' style had evolved considerably. In 'Leisure Hours' (the quotation marks are the painter's) he has painted the Pender sisters as perfect ornaments, trapped in enforced idleness just as much as the goldfish in the bowl in front of them. The paintwork is a little looser and without distractions. The blank stares and suffocating stillness of the composition all add to the narrative, unlike some of his later portraits of women and children, which contrive to be either sickly sentimental or alienatingly haughty.

In his 'Eruption of Vesuvius', minute figures are panic-stricken on the shore, powerless against the great red fury of the volcano.

In his 'Eruption of Vesuvius', minute figures are panic-stricken on the shore, powerless against the great red fury of the volcano.