On the other side of the river used to live a retired Doctor who made good money as a Crematorium Medical Referee. He gave permission for thousands of cremations until it was his turn to go up in smoke. A friend's father was a worker there, once the electrically operated curtain closed around the coffins. Another friend had a summer job at the Crematorium, cutting the grass on the remembrance lawns. He joked about the corpses rising out of coffins as the furnace lit, and the taste of ash in his mouth as the mower trimmed the grass. The crematorium is a smooth-running production line, twenty minute slots, one entrance for the bereaved, another exit, the next party already lined up outside.

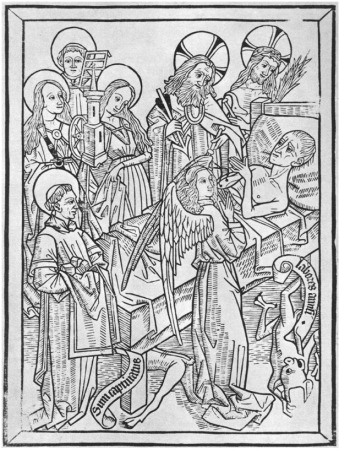

While some make their living out of it, most of us like to avoid thoughts of death. In plague-ravaged 15th century Europe people felt differently. Ars Moriendi (The Art of Dying) was the most popular block-printed book. It gave simple instructions on how to meet death, avoid temptation, and make a triumphal entrance into Paradise.

People often say how quiet it is at night here, since we are less than three miles from Reading town. But the night is far from silent: aircraft into Heathrow, motorbikes along the main road, and late night trains, slicing the air, tearing down into Brunel's great cutting, four years to build and four lives lost.

At around 3.30am these sounds fade. This is the 'dead of the night'. On a windless night, you may just hear the clock on the church tower strike the hour. Most nights there is only the river, falling five feet over the weir. This is white noise, indifferent and unchanging, seemingly endless - the roaring sum of all sound and the sound of nothing.

In the crematorium chapel, there is a different kind of quiet, almost solid silence, stifling. Dark oak, the lectern and pews, and an organ. At my aunt's funeral a friend played Jerusalem for us at the end of the short service. William Blake's words, written in 1804 as a preface to his epic poem 'Milton'. Blake recalls the myth of a young Christ in Glastonbury and looks to a second coming when paradise will be attained. The music by Parry, for a rally of the votes for women campaign in 1918, with orchestral elaboration by Elgar. The organ played loud and strong, drowning our voices, making our hearts pound, filling the silence, and for a moment, there was hope.

What a pity it would be if the authorities were to strip out the organ and replace it with a juke box for hymns.

crematorium

-

Crematorium loses organ