Is it just me? I like old blanket labels. The design of some of these little scraps of silky cloth is fascinating. This 1950s blanket with its evocative label was brought by sea all the way from Australia over 40 years ago. Because she has a Physician chillproof blanket, the happy lady with the bedside flowers will soon be well again. With that sales pitch and with such a striking embroidered design, it's no wonder they sold.

When they were younger my nieces were obsessed with the silky feeling of all kinds of labels. On blankets or teddy bears or sewn into clothing, stroking them was the perfect comforter. 'Continental quilts' (with all their associations of bright sunlit roms and Scandinavian health and efficiency) are all very well, but on a really chilly night you can't beat the comfort of a really good heavy woollen blanket.

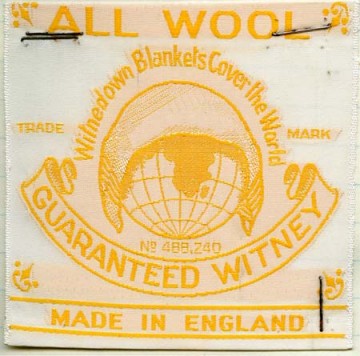

Here in Oxfordshire there was a long tradition of blanket making (they used 'tenter hooks' that are the origin of the familiar phrase). An excellent site, from which some of these images are taken, describes how until the last factory closed in 2002 the Witney blanket was a byword for quality. Made using local wool with a soft spun yarn that formed a fleecy pile, they were widely imitated until a trades descriptions case in 1907 put a stop to such 'passing off'.

Here in Oxfordshire there was a long tradition of blanket making (they used 'tenter hooks' that are the origin of the familiar phrase). An excellent site, from which some of these images are taken, describes how until the last factory closed in 2002 the Witney blanket was a byword for quality. Made using local wool with a soft spun yarn that formed a fleecy pile, they were widely imitated until a trades descriptions case in 1907 put a stop to such 'passing off'.

At its height, thousands of people were worked in the blanket making industry in Witney. The museum there holds a guardbook which contains over 150 blanket label designs used by just one manufacturer in the town.

A special kind of Witney blanket was sold to the hugely powerful Hudson's Bay Company in Canada which traded them with native Americans for beaver furs. These point blankets are an early example of a graphical language being developed to symbolise a product standardisation system. The blankets were graded according to their size and warmth using a system of striped marks which showed up when the folded blankets were stacked together.

A special kind of Witney blanket was sold to the hugely powerful Hudson's Bay Company in Canada which traded them with native Americans for beaver furs. These point blankets are an early example of a graphical language being developed to symbolise a product standardisation system. The blankets were graded according to their size and warmth using a system of striped marks which showed up when the folded blankets were stacked together.

There is a full description of the grading system on the Hudson's Bay Company website.

In November 1779, M. Maugenest met with the Board at Hudson's Bay House in London to deliver his "Proposals of the Terms" under which he would enter into Hudson's Bay Company's service. He offered several suggestions for improving the growing inland trade from Fort Albany along the west coast of James Bay. The sale of "pointed" blankets was one of his suggestions. By December 1779, the sample blankets had been received by the Committee and an order was issued for 500 pairs of "pointed" blankets; 100 pairs of each, in 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5 and 3 point sizes. Although blankets had been a staple of the fur trade to the natives and Hudson's Bay Company men prior to 1780, it was not until the first shipment to Fort Albany in the spring of that year that they were shipped to the posts on a regular basis.

By 1860 full standardization of both sizes and colours had been established.