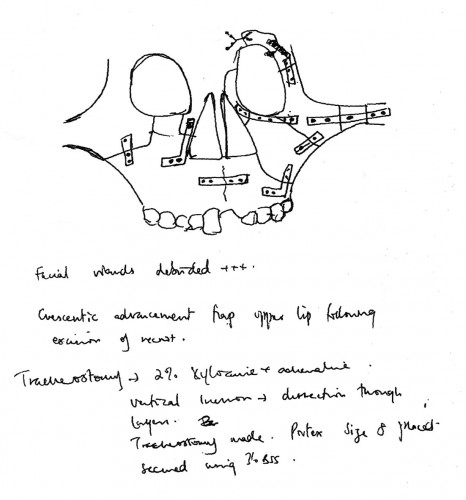

I have breaks but I'm not broken. This particular butterfly is re-emerging, almost nine months after a devastating cycling accident. I was knocked off by a hit-and-run driver, who left me unconscious in a ditch with a smashed face that took 12 hours of surgery to put right.

Thanks to seven or so titanium implants and more screws than I want to count, the cracked bones are back in place. I didn’t get a new front tooth at Christmas, but an implant or bridge will eventually sort that. Weeks of physiotherapy have strengthened weak muscles and restored almost all normal movement. The aches and pains have almost all faded. I’ve been incredibly lucky. The medical team were fabulous, and so were so many friends, who buoyed me up and helped me through the most difficult time.

For a good reason, perhaps, my mind was wiped clean of almost all memories of the accident and the first few days of my recovery. Now I've time to reflect on what happened and what it means for the rest of my life.

My bike had lights and good reflectors and I remember that minutes before the accident I was cycling safely. So why did I choose to cycle down an unlit road late at night without the luminous clothing I normally wear? The answer is that being seen at night was the last thing in my head when I set off for Paris on a sunlit afternoon a few days earlier.

Like most adult male cyclists, I wasn't in the habit of wearing a helmet either – and this is my legal right. Fortunately I sustained no injuries to the part of my skull a helmet would have covered.

I've always thought of myself as optimist, and someone who is by nature happy. Previously, long rides from Lake Garda to Venice, Florence to Sienna and the Hague to Bruges had all been without incident. Why should a 15 minute ride home be any different? This happy optimism turned out to be more than a little misplaced.

Inevitably, research has shown those who are happy really do die younger, perhaps because of a more happy-go-lucky attitude to risk. In addition, one in five Britons and half of all other Europeans are thought to be infected by toxoplasmosis, an ingenious parasite that lodges permanently in our brains, modifying our behaviour so that we are more likely to do dangerous things that might be to the parasite's advantage.

Read the press coverage of cycling behaviour and the emphasis is almost always on making cyclists ride safer (often with the implication that they are irresponsible), not on making motorists pay proper attention.

My perception of the risks of cycling has changed dramatically, as it should perhaps in other areas of my life. Cycling always seemed the most innocent and carefree of activities. But the truth about cycling, as James Cracknell and several friends have found out recently, is quite different. One set of statistics claims the length of time one would have to travel to have a one in a million chance of being killed is:

By air – 4,300 hours; By car – 10 hours; By pedal cycle – 2 hours & 40 minutes

So if you ride, ride as safely as you can manage. A helmet won't stop you getting killed, but it may prevent brain injuries. Be aware of the risks. And when you drive, always be on the look out for cyclists. Please.