Violet Trefusis urged: 'be wicked, be brave, be drunk, be reckless, be dissolute, be despotic, be an anarchist, be a religious fanatic, be a suffragette, be anything you like, but live the gamut of human experiences: build, destroy, build up again! Let's live as none ever lived before, let's tread fearlessly where even the most intrepid have faltered and held back'

Violet Trefusis urged: 'be wicked, be brave, be drunk, be reckless, be dissolute, be despotic, be an anarchist, be a religious fanatic, be a suffragette, be anything you like, but live the gamut of human experiences: build, destroy, build up again! Let's live as none ever lived before, let's tread fearlessly where even the most intrepid have faltered and held back'

Some of her wickedest and most intrepid moments may have been at the Villa Cimbrone in Ravello on the Italian Amalfi coast, where I took a recent holiday.

Trefusis (1894-1972) partied there with her lover Vita Sackville-West. Other guests in this medieval fantasy villa were Forster, Strachey, Keynes, Woolf, Lawrence, Henry Moore and TS Elliot - and even Garbo conducted an affair here. The marvellous garden is thought to be partly Sackville-West's work. Villa Cimbrone was built in 1905 by Ernest Beckett, 2nd Lord Grimthorpe, with the help of his tailor and valet, Nicola Mansi, who went on to become the village's mayor.

Gide said Ravello was 'closer to the sky than the sea'. The centre of the village is perched on a ridge of volcanic tufa which rises 335m above the sea. Inside the duomo we saw a phial of St Pantaleone's blood. In a letter Cadinal Newman wrote in amazement that "the blood of St. Pantaloon... is not touched—but on his feast in June it liquefies. And more, there is an excommunication against those who bring portions of the True Cross into the Church. Why? Because the blood liquefies, whenever it is brought". In the garden at the Villa Cimbrone we took a long walk through tall umbrella pines - the 'Alleé of Immensity' - to the 'Belvedere of Infinity': a stone parapet with white statues and a dazzling view of the entire bay of Salerno. In 1917 Grimthorpe was buried close by, beneath the temple of Bacchus he created.

Gide said Ravello was 'closer to the sky than the sea'. The centre of the village is perched on a ridge of volcanic tufa which rises 335m above the sea. Inside the duomo we saw a phial of St Pantaleone's blood. In a letter Cadinal Newman wrote in amazement that "the blood of St. Pantaloon... is not touched—but on his feast in June it liquefies. And more, there is an excommunication against those who bring portions of the True Cross into the Church. Why? Because the blood liquefies, whenever it is brought". In the garden at the Villa Cimbrone we took a long walk through tall umbrella pines - the 'Alleé of Immensity' - to the 'Belvedere of Infinity': a stone parapet with white statues and a dazzling view of the entire bay of Salerno. In 1917 Grimthorpe was buried close by, beneath the temple of Bacchus he created.

Celebrity connections with Ravello don't stop at the Villa Cimbrone. On an inaccessible ridge directly below it is La Rondinaia, built in 1930 by Mansi for Grimthorpe's second daughter. Until infirmity forced him to move back to the US, it was Gore Vidal's home. A local told us how he used to sit in his wheelchair in Ravello's main square, entertaining visitors with his wisecracks and belying his local reputation for cantankerousness.

We ate lunch in the garden of the Villa Maria, one of three hotels owned by Vicenzo Palumbo. The patron himself was in orange trousers, idly tending flowers while his staff ran the place for him. With two others he has bought La Rondinaia, reputedly for more than £10m, and plans to turn it into a Vidal museum and luxury hotel.

We ate lunch in the garden of the Villa Maria, one of three hotels owned by Vicenzo Palumbo. The patron himself was in orange trousers, idly tending flowers while his staff ran the place for him. With two others he has bought La Rondinaia, reputedly for more than £10m, and plans to turn it into a Vidal museum and luxury hotel.

A PILGRIM SITE

Set below La Rondinaia is a church dedicated to the twin saints Cosmas & Damian. We visited on a long walk from Amalfi. I took no photos inside, since this was so evidently a living church: we passed two frail women walking with difficulty up the steps to the church for the evening service.

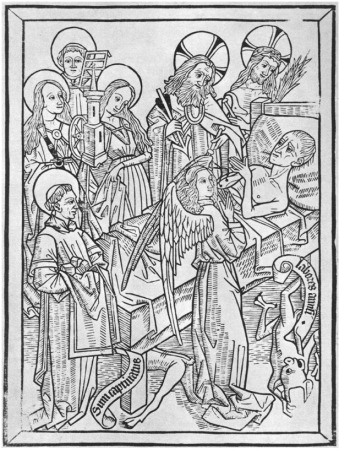

Cosmas & Damian practised as doctors in Asia Minor in the third century, and taking no money for their cures, drew many to the faith. During Diocletian's persecutions they were tortured to death. Their relics became popular with pilgrims and in Ravello many have left ex-voto offerings in gratitude for medical cures attributed to the patron saints of medicine.

Hundreds of silver plaques represent every part of the body thought to have been healed by the saints: legs, and arms, teeth, and breasts, hearts and brains all cut out in silver and hanging on red silk in glass cases.

Hundreds of silver plaques represent every part of the body thought to have been healed by the saints: legs, and arms, teeth, and breasts, hearts and brains all cut out in silver and hanging on red silk in glass cases.

MUSIC AND WALKING

Besides the Villa Cimbrone, Ravello's other jewel is the Villa Rufolo, also with gardens designed by a Briton. Rufolo is a half-ruined 13th-century palazzo, the venue for highly successful arts festivals. The garden inspired Wagner's dream of a magical garden in Parsifal.

On our last night on the Amalfi coast we heard a clarinet and piano recital at the Villa before walking down the hillside to our accommodation in Minori, right by the sea. The twisting path took us down steps through lemon and olive groves, across the echoing porchways of several ancient churches and finally past Minori's necropolis, glimpsed through high gates, each decorated with skull and cross-bones.

The walled cemetery was bathed in blue light. Three terraces, one stone slab set into the wall for each family, lines of slabs stacked so high that a ladder is needed to look after the photos and flowers and the little electric light that burns night and day on each. With the scent of ripe figs and the tufa grey soil in the air we descended happily to the moonlit sea.

The walled cemetery was bathed in blue light. Three terraces, one stone slab set into the wall for each family, lines of slabs stacked so high that a ladder is needed to look after the photos and flowers and the little electric light that burns night and day on each. With the scent of ripe figs and the tufa grey soil in the air we descended happily to the moonlit sea.

A SWIM AT DUSK

One evening just before dusk I walked down to the beach at Minori. The passegiata would soon be in full swing: that special time in the evening when ordinary Italians dress up and go out for a stroll and to chat. On the beach a few kids kicked a football about, but I was the only swimmer. The sea was warm, the surface calm. I swam out 100 metres or more from the shore. Just above the town a blue neon cross marked the cemetery and beyond I saw the line of white lights - like a string of twinkling pearls - marking the path all the way up to Ravello. Higher up there were lights at SS Cosmas & Damiano, too - an orange glow that floodlit the cliff above. Higher still I could even see La Rondinaia - floodlit with a steady bright white light - and thought I caught a glimpse of the fabulous belvedere at the Villa Cimbrone.

On the beach, feeling a cool breeze, I showered and changed. Someone asked me if the water was cold. 'Not at all - it's warm!'. Feeling content, I suddenly remembered Homer's magical line about the 'wine-dark sea' and watched an almost full moon shimmering silver on its surface.

On the beach, feeling a cool breeze, I showered and changed. Someone asked me if the water was cold. 'Not at all - it's warm!'. Feeling content, I suddenly remembered Homer's magical line about the 'wine-dark sea' and watched an almost full moon shimmering silver on its surface.

The three of us are walking on Dartmoor on a dull day in early September. We climb up from Burrator Reservoir, with its moss covered boulders and lichen covered trees, to a spot high on the bare moor where we picnic beside

The three of us are walking on Dartmoor on a dull day in early September. We climb up from Burrator Reservoir, with its moss covered boulders and lichen covered trees, to a spot high on the bare moor where we picnic beside