A worthwhile post on English Buildings drew my attention to Ronald Lampitt's illustrations in The map that came to life, a children's book first published by OUP in 1948. Elsewhere there's also a complete set of spreads and a page about Lampitt's map of an ideal city.

A worthwhile post on English Buildings drew my attention to Ronald Lampitt's illustrations in The map that came to life, a children's book first published by OUP in 1948. Elsewhere there's also a complete set of spreads and a page about Lampitt's map of an ideal city.

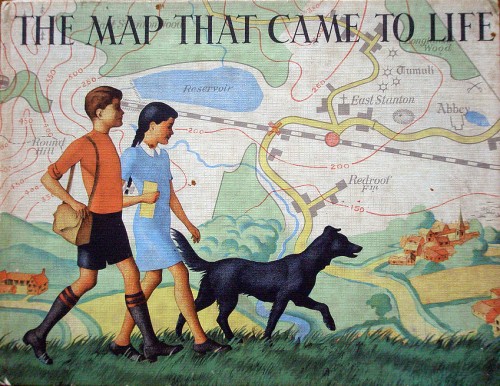

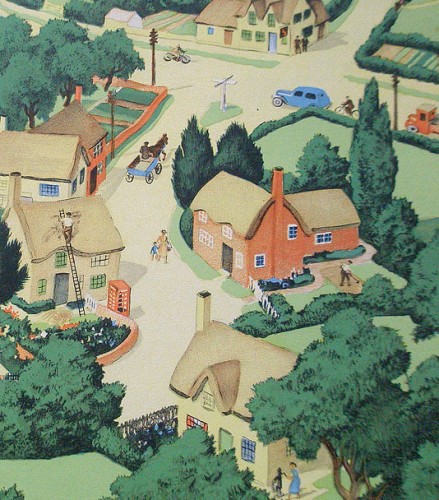

The beautifully illustrated cover is slightly reminiscent of Seurat's 'La Grande Jatte', without the pointillism. The book celebrates the fascination of maps as graphical language - ways of representing in two dimensions the richness of the real world. Lampitt paints the archetypal romantic (and very idealised) English village, set in a perfect landscape:

"These two children set off on a walk across unfamiliar country with only their map for guidance. They talk to strangers – who give them fascinating nuggets of local information rather than luring them into dark corners. Their dog spends most of its time off its lead, rivers and lakes hold no terrors for them, and, of course, this being 1948, they are not much troubled by traffic."

Lampitt also worked for Ladybird, including the 1967 title Understanding maps, but information on him is scarce. Google Earth can't compete with Lampitt's golden vision of English Never-Never-Land.

Lampitt also worked for Ladybird, including the 1967 title Understanding maps, but information on him is scarce. Google Earth can't compete with Lampitt's golden vision of English Never-Never-Land.  Secondhand copies appear rarely. A reprint is certainly overdue.

Secondhand copies appear rarely. A reprint is certainly overdue.

Comments

It’s good to see this, David. A few years ago I illustrated ‘The map that came to life’ in a talk to the Imprint Society of Reading as an example of the kind of visual narrative and explanation that, in Britain, emerged during the second world war (e.g. in Puffin Picture Books) and which flourished for some time afterwards. The author, H. J. Deverson, explains that this is ‘a picture story, for as you read the words which describe the walk, you see drawings on the same pages which show exactly where the children and their dog went.’

The book came out from OUP in 1948. That was the year in which, in June, the Empire Windrush, with 492 passengers from the Caribbean, docked at Tilbury, and in the same month the cold war began with a crisis in Berlin. In the following month, the National Health Service and National Insurance were simultaneously launched.

It was also the year in which Marshall Tito steered Yugoslavia away from the Soviet Union with a policy of ‘positive neutralism’. I mention this because a colleague at the time of that Imprint Society talk was from Slovenia, once part of soft-communist Yugoslavia. When she saw these pictures of John and Joanna, the young actors in Lampitt’s evocative pictures, she confirmed immediately my identification of them not as rural middle-class kids from The Archers (which started two years later) but as Young Pioneers, striding with confidence and optimism into the future. Only the red neckerchiefs are missing. Their dog is, of course, called Rover.