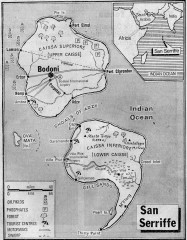

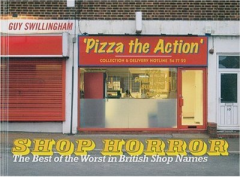

The predeliction of English salons for this kind of linguistic tomfoolery is so great that they made up a good part of a Guy Swillingham's Shop horror: the best of the worst in British shop names. If you can excuse a comment about one map which is made up of 'mere typography' Strange Maps has many other gems, including a description of the Guardian's April 1977 feature on San Seriffe

The predeliction of English salons for this kind of linguistic tomfoolery is so great that they made up a good part of a Guy Swillingham's Shop horror: the best of the worst in British shop names. If you can excuse a comment about one map which is made up of 'mere typography' Strange Maps has many other gems, including a description of the Guardian's April 1977 feature on San Seriffemaps

-

Hair affairs

From the site Strange Maps comes this record from Die Zeit of the popularity of awful puns in the names of German hairdressing salons. The most popular is 'Haarmonie'. The others uphold that unfortunate line about the missing Germanic funny bone: Haareszeiten puns on Jahreszeiten - which means seasons - and Haargenau just means 'exactly' in the sense of 'to a hair'.Enertaining whimsy, including the menacing hairy outer darkness surrounding Germany, but not very effective map-making. I wanted the map to be dynamic, revealing photos of shop signs, much like the ones featured in the Hairdressers With Funny Names Pool on Flickr. The predeliction of English salons for this kind of linguistic tomfoolery is so great that they made up a good part of a Guy Swillingham's Shop horror: the best of the worst in British shop names. If you can excuse a comment about one map which is made up of 'mere typography' Strange Maps has many other gems, including a description of the Guardian's April 1977 feature on San Seriffe

The predeliction of English salons for this kind of linguistic tomfoolery is so great that they made up a good part of a Guy Swillingham's Shop horror: the best of the worst in British shop names. If you can excuse a comment about one map which is made up of 'mere typography' Strange Maps has many other gems, including a description of the Guardian's April 1977 feature on San Seriffe -

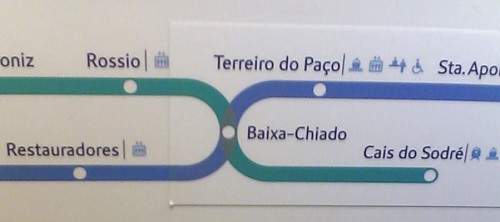

Following the diagram in Lisbon

In Lisbon I much enjoyed the metro system, which is full of art and something of which the city is clearly proud. Its diagram uses Metrolis, a custom font from The Foundry. The lines are called seagull, sunflower, caravelle and orient: they have over-fussy graphics that don't quite fit the clean diagram. On the trains themselves the maps can get interesting too. I'm not colour blind but couldn't quite work out why the linear maps seem to turn in on themselves so much. Metrobits.org has a page which lists the fonts used in some 17 metro systems and (if you're listening Santa) I now have to add Metro Maps of the World (new edition, Mark Ovenden) to my Christmas list. -

Lampitt's living maps

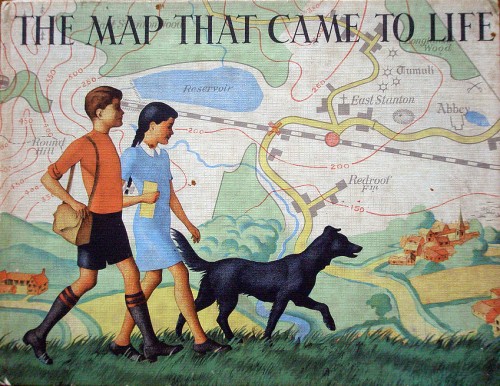

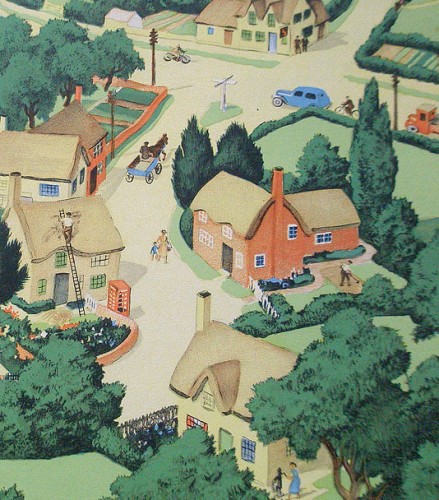

A worthwhile post on English Buildings drew my attention to Ronald Lampitt's illustrations in The map that came to life, a children's book first published by OUP in 1948. Elsewhere there's also a complete set of spreads and a page about Lampitt's map of an ideal city.

A worthwhile post on English Buildings drew my attention to Ronald Lampitt's illustrations in The map that came to life, a children's book first published by OUP in 1948. Elsewhere there's also a complete set of spreads and a page about Lampitt's map of an ideal city.The beautifully illustrated cover is slightly reminiscent of Seurat's 'La Grande Jatte', without the pointillism. The book celebrates the fascination of maps as graphical language - ways of representing in two dimensions the richness of the real world. Lampitt paints the archetypal romantic (and very idealised) English village, set in a perfect landscape:

"These two children set off on a walk across unfamiliar country with only their map for guidance. They talk to strangers – who give them fascinating nuggets of local information rather than luring them into dark corners. Their dog spends most of its time off its lead, rivers and lakes hold no terrors for them, and, of course, this being 1948, they are not much troubled by traffic."

Lampitt also worked for Ladybird, including the 1967 title Understanding maps, but information on him is scarce. Google Earth can't compete with Lampitt's golden vision of English Never-Never-Land.

Lampitt also worked for Ladybird, including the 1967 title Understanding maps, but information on him is scarce. Google Earth can't compete with Lampitt's golden vision of English Never-Never-Land.  Secondhand copies appear rarely. A reprint is certainly overdue.

Secondhand copies appear rarely. A reprint is certainly overdue.