They say that the sense of smell is the most evocative: the brain is so wired that the connection between memory and odour is the most direct. The smell of a certain floor polish instantly takes me back to school days, when a big polishing machine with soft spinning disks was always swung over the wooden floors at the end of the day.

This Christmas it was the sense of touch that connected me to the past. Reading The Cottage Smallholder's post about making your own butter I decided to try to make some for the brandy butter. Soured cream 'churned' in a food processor suddenly 'breaks' into little pieces of butter. Wash it in iced water, place on a cold marble slab. Pat into shape. A rhythm soon develops, the pat slapped this way and that, residual buttermilk flowing out - the movements reassuring, not learned, but somehow bred in the bone - instinctive and natural. My mother helped for a while and remembered that the last time she had made butter pats was 70 years before, at her grandmother's at Fengate, long since bulldozed for the Peterborough ringroad.

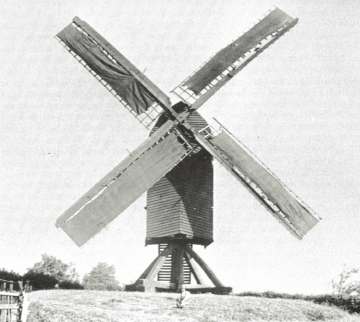

The mill house at Fengate was already rubble the first time I saw my Great Uncle Joe Hinkins. We children glimpsed the demolition site by peering through a high fence. We were told how Joe and his 12 siblings had been brought up in a beautiful, ancient, rambling house there. The old windmill had burnt down in a notorious fire in 1919. Joe now lived in Chestnut House next door, where we were fascinated by the gorgeous peacocks wandering round the yard. His father dealt in horses, and famously once filled his bowler hat with gold sovereigns after a particularly successful day's trading on Peterborough market. Young Joe kept the horse and cart outside the pub while his father drank the profits. When he grew up Joe was a sworn tee-totaller.

When it was his turn to continue the family business, Joe kept on a few cows and the dairy where a rat infected with Weil's disease killed another great uncle. As Peterborough spread closer, Joe sold some of the fields to the football club but leased them back for grazing. He still went to horse fairs, and kept an interest in several race horses. Several times he took us racing. But given that progress could not be denied, Joe dealt in secondhand cars, building up a successful business on the site of the old farmyard.

Everyone knew him as the kindest of men, given to spontaneous acts of generosity. Once, quite without warning, a harmonium turned up at our house. Joe thought we might like it. The story goes that when he became ill, one relative called a lawyer, not a doctor and talked the old man into changing his will solely in his favour. Aged just 66, Joe died soon after, in June 1977. The local gypsies, to whom he had been so generous, turned out in their finest clothes, standing silently all along the way from Chestnut House to the funeral.

Buy Windmills of Northamptonshire at Amazon

Given John Prescott MP's unlikely reputation as a lothario, it seems right that he be remembered for giving permision for London's most thrusting new erection - Renzo Piano's 'shard of glass' at London Bridge. Piano describes it as "a vertical town for about 7,000 people" based on "London's heritage of masts and towers".

Given John Prescott MP's unlikely reputation as a lothario, it seems right that he be remembered for giving permision for London's most thrusting new erection - Renzo Piano's 'shard of glass' at London Bridge. Piano describes it as "a vertical town for about 7,000 people" based on "London's heritage of masts and towers".

In his 'Eruption of Vesuvius', minute figures are panic-stricken on the shore, powerless against the great red fury of the volcano.

In his 'Eruption of Vesuvius', minute figures are panic-stricken on the shore, powerless against the great red fury of the volcano.

The unfashionable Cornish poet and playwright Charles Causley died in 2003. At an Advent service in

The unfashionable Cornish poet and playwright Charles Causley died in 2003. At an Advent service in