Where else but at Calshot Bay, a little known stretch of coast close by Fawley power station in Hampshire, where the great liners still slip out of Southampton Water, dwarfing beach huts to the size of matchboxes, and an annual cricket match takes place on a sandbank two miles out to sea?

William and I motored down last weekend and spent a pleasant few hours re-acquainting ourselves with the pleasures of this gloriously eccentric place. I was promised a fishing trip by an amiable ruddy-faced 'sea dog' from Farnborough and we swam with a man whose boyfriend of ten years was wanted by the Police in Reading and 'of NFA - no fixed abode'. The fisherman had bought his beach hut from the wife of the film director Ken Russell, whose family own a line of the grander huts at the west end of the beach.

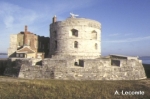

Calshot Spit was home to Lawrence of Arabia, when he was stationed at the RAF base there. Here is a castle built in 1540 to defend Southampton Harbour, which was even then one of the largest ports in the land. The last ever Schneider Cup flying boat races were held here and a giant Grade II* listed hangar from 1917 is named after the Sopwith Camel, said to be one of the finest fighter planes of the First World War. Cyclists now race where the aircraft stood as the hangars house an echoing velodrome that is part of the Calshot Activities Centre.

Calshot Spit was home to Lawrence of Arabia, when he was stationed at the RAF base there. Here is a castle built in 1540 to defend Southampton Harbour, which was even then one of the largest ports in the land. The last ever Schneider Cup flying boat races were held here and a giant Grade II* listed hangar from 1917 is named after the Sopwith Camel, said to be one of the finest fighter planes of the First World War. Cyclists now race where the aircraft stood as the hangars house an echoing velodrome that is part of the Calshot Activities Centre.

We chatted in the Bluebird - Calshot's tiny beach café, named after a Schneider craft - watching the confusion of boats moored around a cricket match being played on the Brambles sand bar two miles out in the Solent. This truly bizarre institution takes place for only about an hour on just one day a year. There is (barely) enough dry land for players from two sailing clubs on the Isle of Wight and at Southampton to take their runs against a backdrop of supertankers.

We chatted in the Bluebird - Calshot's tiny beach café, named after a Schneider craft - watching the confusion of boats moored around a cricket match being played on the Brambles sand bar two miles out in the Solent. This truly bizarre institution takes place for only about an hour on just one day a year. There is (barely) enough dry land for players from two sailing clubs on the Isle of Wight and at Southampton to take their runs against a backdrop of supertankers.

Earlier we had been politely asked to leave a stretch of protected beach by two well-spoken fellows in cream chinos and blue Oxford shirts - summer uniform of the young upper class male - one of whom (I think) turned out to be a scion of the Drummond family, who made their money as royal bankers. The family own the Cadland Estate. Just before I had chatted to an estate worker with a pleasant Hampshire burr who said he was down on the beach to check out the fishing.

The water was pleasantly warm and shallow as William and I swam together from the far end of the beach to the steps of Luttrell's Tower, a splendid 18th century folly now owned by the Landmark Trust. On the drive home the sun set spectacularly behind power pylons, but all my thoughts were of the glories of the English seaside.

The water was pleasantly warm and shallow as William and I swam together from the far end of the beach to the steps of Luttrell's Tower, a splendid 18th century folly now owned by the Landmark Trust. On the drive home the sun set spectacularly behind power pylons, but all my thoughts were of the glories of the English seaside.

diaphania - Page 11

-

Royal bankers, the Brambles & a Bluebird

-

Transfigured in St Paul's?

To St Paul's in London for a Saturday service on the Feast of the Transfiguration. Friends from Schola Aquae Sulis sang music by Howells and the sermon asked for prayers 'for this beautiful but broken world' on the 60th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima.

To St Paul's in London for a Saturday service on the Feast of the Transfiguration. Friends from Schola Aquae Sulis sang music by Howells and the sermon asked for prayers 'for this beautiful but broken world' on the 60th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima.

Transfiguration - when Christ's clothes became dazzling white and a voice said 'this is my Son, listen to Him' was the theme, with a parallel with moments of transfiguration in our own lives.

The sermon quoted research documenting instances of theophany: moments when the divine is suddenly made visible. In landscape, when the light changes and everything seems for an instant transformed, at peace and whole – I have experienced these feelings.

Were there moments like these in the service, when incense mixed with incantatory chants, and light shone on a distant cross on the high altar, music wove a spell and the great cathedral became much more than a glitteringly grandiose tourist attraction?

Music has this power to move and transform me. It was like this in a late night Prom in the Royal Albert Hall last Thursday. The Canadian counter tenor Daniel Taylor sang the Handel aria 'Cara sposa, amante cara' from Rinaldo. The piteous, plaintive threads of music seemed to shape filigree patterns in the air around us, drawing together audience and performer in a moment of great stillness and beauty.

But are these 'feelings' real - whatever that means? They might not withstand scientific examination, but it seems to me that there is a transforming power in these humbling moments of transfiguration that can inform our whole lives.

Tentatively I pray this hope can endure amid all our cruelty and greed and selfishness. -

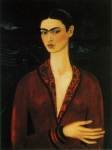

Kahlo at the Tate

For André Breton 'the art of Frida Kahlo is a ribbon about a bomb'. A major exhibition at the Tate Modern (to 9 October, 2005) features her powerful work. Many have been gripped by the fascination of Frida Kahlo: not because it is intensely beautiful or hugely grand but because it is deeply personal, intensely vivid and raw. Red raw even with her own blood and with her own tears that fall in self-portraits where her body - maimed by a violent accident that cast its shadow across her life - lies ripped open. Her beautiful face lingers most in the memory. Her expression is proud, resigned and defiant. She is vulnerable and yet composed, face half-turned away from her viewer.

For André Breton 'the art of Frida Kahlo is a ribbon about a bomb'. A major exhibition at the Tate Modern (to 9 October, 2005) features her powerful work. Many have been gripped by the fascination of Frida Kahlo: not because it is intensely beautiful or hugely grand but because it is deeply personal, intensely vivid and raw. Red raw even with her own blood and with her own tears that fall in self-portraits where her body - maimed by a violent accident that cast its shadow across her life - lies ripped open. Her beautiful face lingers most in the memory. Her expression is proud, resigned and defiant. She is vulnerable and yet composed, face half-turned away from her viewer.

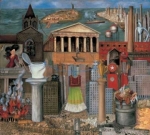

In her marriage to the muralist Diego Rivera she found the basis for an enduring connection with the Mexican soil and its ancient people. Mexican pitahaya fruit plump erotically and are pierced by needle sharp flags like the steel that shattered her spine and took away her womb.

There is duality in her attempt to square her European father with her campesina mother: stiff colonial dresses are juxtaposed with the peasant costume that was her trademark. Duality in her bisexuality too, and in My Dress Hangs There, 1933 which illustrates her antithesis to American 'Fordism' with its concrete factories and obsession with sport and hygiene. Her sense that she sprang from the Mexican soil and that she would return to it gave her hope of a kind of reincarnation. This powerful spirituality, which fused east and west and placed both Gandhi and Hitler in her pantheon, provided an enduring message of hope, carved out of Kahlo's despair and desperate adversity.

There is duality in her attempt to square her European father with her campesina mother: stiff colonial dresses are juxtaposed with the peasant costume that was her trademark. Duality in her bisexuality too, and in My Dress Hangs There, 1933 which illustrates her antithesis to American 'Fordism' with its concrete factories and obsession with sport and hygiene. Her sense that she sprang from the Mexican soil and that she would return to it gave her hope of a kind of reincarnation. This powerful spirituality, which fused east and west and placed both Gandhi and Hitler in her pantheon, provided an enduring message of hope, carved out of Kahlo's despair and desperate adversity.

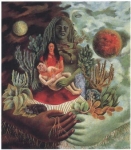

The cosmology of the Love-Embrace of the Universe (1949), in which she cradles Diego as naked adult foetus while she too is cradled by the Mexican earth goddess who in turn is wrapped by a female sun and moon, seemed a most poignant encapsulation of her spiritual journey.

The cosmology of the Love-Embrace of the Universe (1949), in which she cradles Diego as naked adult foetus while she too is cradled by the Mexican earth goddess who in turn is wrapped by a female sun and moon, seemed a most poignant encapsulation of her spiritual journey.As the light faded that afternoon I swam great circles in the men's pond on Hampstead Heath. Trees hid the broad pond from London and the water was sweet with an earthy murkiness.

-

Skinny-dipping at the West Blockhouse

Undiscovered Pembrokeshire and the Landmark Trust's stunning West Blockhouse provided a terrific location for a holiday during the hottest week of July. Built in 1857 to defend Milford Haven, the second largest natural harbour in the world (the other is in New York), the fort is built from great slabs of impeccably jointed marble and limestone. A moat and narrow drawbridge protect it from attack.

Undiscovered Pembrokeshire and the Landmark Trust's stunning West Blockhouse provided a terrific location for a holiday during the hottest week of July. Built in 1857 to defend Milford Haven, the second largest natural harbour in the world (the other is in New York), the fort is built from great slabs of impeccably jointed marble and limestone. A moat and narrow drawbridge protect it from attack.Six of us walked the coast and swam from deserted coves. We sat about reading and played each other music, cooking huge meals in the fort's panelled rooms, impeccably furnished in period and hung with military prints and portraits of vaguely disapproving military gents. The last soldiers left at the end of the Second World War. One officer loved the place so much he told his men they should be paying to stay there. On arrival we ran like delighted children from room to room, breathing in the smell of beeswax and lavender polish, catching new vistas of sparkling sea from every narrow window.

The views out across the water are stunning. Three distant oil refineries flare at night. Three giant radio beacons above the fort guide in the huge tankers which pass close enough for one group of Norwegian mariners to wave at us. Some of the rocks still bear the traces of the catastrophic oil spill from the wreck of the Sea Empress in 1996. The nearby islands of Skomer, Grassholm and Ramsey provide havens for wildlife including the seals we looked so hard for but never spotted. Along the coast-paths, soil banks built to protect the fields were like a carefully planted rock garden, with bee orchids, daisies and willow herb in full bloom.

The views out across the water are stunning. Three distant oil refineries flare at night. Three giant radio beacons above the fort guide in the huge tankers which pass close enough for one group of Norwegian mariners to wave at us. Some of the rocks still bear the traces of the catastrophic oil spill from the wreck of the Sea Empress in 1996. The nearby islands of Skomer, Grassholm and Ramsey provide havens for wildlife including the seals we looked so hard for but never spotted. Along the coast-paths, soil banks built to protect the fields were like a carefully planted rock garden, with bee orchids, daisies and willow herb in full bloom. The roof of the fort was a scorching sun trap where we flew the Union Flag each morning. One night I walked down to Watwick Bay just ten minutes away. Steep steps lead to soft white sand, the lapping waves and the musk smell of wild honeysuckle. I swam alone and walked back close to midnight, still undressed in the warm night air.

The roof of the fort was a scorching sun trap where we flew the Union Flag each morning. One night I walked down to Watwick Bay just ten minutes away. Steep steps lead to soft white sand, the lapping waves and the musk smell of wild honeysuckle. I swam alone and walked back close to midnight, still undressed in the warm night air. -

Street life and the ambassadors in Marrakech

A riad in the heart of the medina where purple bourganvillea trails from a roof garden to a cool tiled courtyard. Street cries heard from our room: the man with fresh sardines, silver and shining on the back of his bike pushed through 30 degrees of heat, another calling to collect old bread, someone else collecting rags. Rich smells catch in the nostrils from a spice store nearby. Scarlet-costumed water sellers and story tellers in the Djamaa el Fna, clouds of dust and smoke from braziers rising upwards with the shrieking of the snake charmers' pipes and the rattle of drums. A twisting maze of narrow streets with a tout on every corner. Stalls piled with spices, carvings, pottery and brasswork in the labyrinthine souk. A baker and a hammam in each district and five times a day the amplified wail of half a dozen competing muzzein. Where else but Marrakech, still medieval for all its internet cafés, thronging with colour and life from dawn to long after dusk.

A riad in the heart of the medina where purple bourganvillea trails from a roof garden to a cool tiled courtyard. Street cries heard from our room: the man with fresh sardines, silver and shining on the back of his bike pushed through 30 degrees of heat, another calling to collect old bread, someone else collecting rags. Rich smells catch in the nostrils from a spice store nearby. Scarlet-costumed water sellers and story tellers in the Djamaa el Fna, clouds of dust and smoke from braziers rising upwards with the shrieking of the snake charmers' pipes and the rattle of drums. A twisting maze of narrow streets with a tout on every corner. Stalls piled with spices, carvings, pottery and brasswork in the labyrinthine souk. A baker and a hammam in each district and five times a day the amplified wail of half a dozen competing muzzein. Where else but Marrakech, still medieval for all its internet cafés, thronging with colour and life from dawn to long after dusk. -

An English country garden

Is there anywhere more gorgeous than an english cottage garden in early summer? Sweet musk from honeysuckle and lilac. Jubilant birdsong at dawn: all the excitement of a new season.

Is there anywhere more gorgeous than an english cottage garden in early summer? Sweet musk from honeysuckle and lilac. Jubilant birdsong at dawn: all the excitement of a new season. -

'What is the point in being a conventional person?'

So said film-maker Ismail Merchant, who died on 25 May aged 68. His belief 'in doing things in the most unorthodox manner' made him a genius at raising funds for films like his favourite 'A room with a view', and for 'Howards End' and 'Maurice'. Often derided, 'costume drama' is nowadays a term of abuse, apparently signifying overly lavish sets, the rustle of crinoline and limp romanticism. But for me there is a joyfulness about some Merchant Ivory productions that is out of sync with our predilection for gloom and complaint. Helena Bonham-Carter's Lucy has a passion for life, for Italy and for love itself that puts her at odds with convention.

So said film-maker Ismail Merchant, who died on 25 May aged 68. His belief 'in doing things in the most unorthodox manner' made him a genius at raising funds for films like his favourite 'A room with a view', and for 'Howards End' and 'Maurice'. Often derided, 'costume drama' is nowadays a term of abuse, apparently signifying overly lavish sets, the rustle of crinoline and limp romanticism. But for me there is a joyfulness about some Merchant Ivory productions that is out of sync with our predilection for gloom and complaint. Helena Bonham-Carter's Lucy has a passion for life, for Italy and for love itself that puts her at odds with convention.

I was in Bruges for a friend's birthday last weekend. After showers we enjoyed the medieval townscape in the just-washed clarity of bright Spring sunshine. Lovers seemd to be everywhere and in the glorious Orangerie it was a little like a Merchant Ivory production. Champagne and smoked salmon from the buffet for breakfast, with a view over the sparkling canal from a richly furnished room in a former convent. Tea from a Georgian silver pot, linen napkins, fresh strawberry and pineapple and little cakes made from the richest Belgian chocolate.

I was in Bruges for a friend's birthday last weekend. After showers we enjoyed the medieval townscape in the just-washed clarity of bright Spring sunshine. Lovers seemd to be everywhere and in the glorious Orangerie it was a little like a Merchant Ivory production. Champagne and smoked salmon from the buffet for breakfast, with a view over the sparkling canal from a richly furnished room in a former convent. Tea from a Georgian silver pot, linen napkins, fresh strawberry and pineapple and little cakes made from the richest Belgian chocolate.

At the Musée Royaux des Beaux Arts, Brussels I loved the loose brushwork and lightness of this painting by Magritte. In the Arentshuis museum in Bruges are paintings and prints by Sir Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) – one of those artists whose work seems due for re-evaluation. His painted work is almost frivolously sunny and optimistic, while his prints are wonderfully dark and brooding. Anglo-Saxon dourness and mistrust of the unfamiliar probably lay behind the rejection of his sumptuous 'British Empire Panels' intended for the House of Lords and finally displayed in the Brangwyn Hall in Swansea. A similar dourness and disapproval of anything arty must be the reason why a relative of mine burnt some of Brangwyn's original drawings, given to a family member who was Brangwyn's chauffeur and one of the first licensed drivers in London.

At the Musée Royaux des Beaux Arts, Brussels I loved the loose brushwork and lightness of this painting by Magritte. In the Arentshuis museum in Bruges are paintings and prints by Sir Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) – one of those artists whose work seems due for re-evaluation. His painted work is almost frivolously sunny and optimistic, while his prints are wonderfully dark and brooding. Anglo-Saxon dourness and mistrust of the unfamiliar probably lay behind the rejection of his sumptuous 'British Empire Panels' intended for the House of Lords and finally displayed in the Brangwyn Hall in Swansea. A similar dourness and disapproval of anything arty must be the reason why a relative of mine burnt some of Brangwyn's original drawings, given to a family member who was Brangwyn's chauffeur and one of the first licensed drivers in London.

One the train home, two young American men with close-cropped hair gazed at each other and kissed and canoodled. Long live unconventionality.

Telegraph obituary for Ismail Merchant

IMDB filmography for Merchant -

'A beautiful life' Gwen John and a family wedding in Wales

'A beautiful life is to be lived in the shadows, but with peace, order and tranquility' - these words by the painter Gwen John (1876-1939) were quoted at an exhibition about her work and that of her brother Augustus which I saw for a second time this weekend. The show was at the National Museum & Gallery in Cardiff. I was there after an idyllic family wedding at the St Pierre Hotel in Chepstow.

'A beautiful life is to be lived in the shadows, but with peace, order and tranquility' - these words by the painter Gwen John (1876-1939) were quoted at an exhibition about her work and that of her brother Augustus which I saw for a second time this weekend. The show was at the National Museum & Gallery in Cardiff. I was there after an idyllic family wedding at the St Pierre Hotel in Chepstow.

Gwen John's words fit both her work and with my experience of a quietly happy and ordered weekend in Wales. She believed profoundly that her art was integral to her faith, and in her last years produced some remarkable understated portraits inspired by a devotional image of Mère Poussepin, the 17th century founder of an order of nuns near her home in Meudon.

These small-scale, chalky portraits have an austere beauty. John's subjects gaze serenely out of narrowly proportioned canvases in muted greys and browns. After an affair with Rodin, the painter lived out her last years in ordered isolation in a pair of little wooden houses surrounded by green. I heard four young harp students give a recital in the gallery. Mussorgsky's Great Gate of Kiev sounded wonderfully dynamic when performed by a harp quartet, overlooked by a portrait by William Parry of his father John, 'The Blind Harper of Ruabon', (d 1782) sometimes called the father of modern harpists.

These small-scale, chalky portraits have an austere beauty. John's subjects gaze serenely out of narrowly proportioned canvases in muted greys and browns. After an affair with Rodin, the painter lived out her last years in ordered isolation in a pair of little wooden houses surrounded by green. I heard four young harp students give a recital in the gallery. Mussorgsky's Great Gate of Kiev sounded wonderfully dynamic when performed by a harp quartet, overlooked by a portrait by William Parry of his father John, 'The Blind Harper of Ruabon', (d 1782) sometimes called the father of modern harpists.

I was delighted by the empty, bright galleries with their collection of remarkable Monets, Renoirs, Cezannes and Sisleys given by the Davies Sisters of Gregynog. Paintings gave glimpses of long dead sitters' lives: the newborn, a family group by Gainsborough, August John's ferocious children, the middle-aged in their prime and Gwen John's serene elderly nuns. I watched the same life stories being told out in Cardiff's shopping streets. In the warm spring sunshine all seemed ordered and peaceful. Even the traffic moved with stately good manners.

Calm good organisation and quiet consideration seemed to mark the wedding, the official start of another couple's life together. It began with a service in the tiny church of St Peter, St Pierre, next to the hotel.

The manor of St Pierre was founded by the Normans and once briefly sheltered the crown jewels. In church the wedding party sat close-by two remarkable 13th century carved tombstones, one of which is believed to commemorate Benet, the church's first known priest. A staff sprouts leaves and is surrounded by wildlife celebrating renewal. Like generations of locals before me I touched the carving's hand that he might bring luck both to me and to the newly married couple.

The manor of St Pierre was founded by the Normans and once briefly sheltered the crown jewels. In church the wedding party sat close-by two remarkable 13th century carved tombstones, one of which is believed to commemorate Benet, the church's first known priest. A staff sprouts leaves and is surrounded by wildlife celebrating renewal. Like generations of locals before me I touched the carving's hand that he might bring luck both to me and to the newly married couple.

Gwen John at the National Museum of Wales

Tate Gallery article about Gwen John -

Caravaggio at the National Gallery

Just 16 paintings in this show, but what an impact they made. I expected the cherry ripe sensuousness of 'Boy with a basket of fruit' (1593-4) but these six dimly-lit rooms focus on Caravaggio's last four years before his death in exile aged just 39, in 1610. Comparison between two versions of the 'Supper at Emmaus', just 5 years apart, showed the transformation from richness and colour to a darker, more humane vision. Caravaggio's stunning chiaroscuro and drama that inspires film-makers like Jarman and Scorsese. In 'The flagellation' of 1607, the tension between Christ's soft submission and the hatred of his scourger is painful to see.

Just 16 paintings in this show, but what an impact they made. I expected the cherry ripe sensuousness of 'Boy with a basket of fruit' (1593-4) but these six dimly-lit rooms focus on Caravaggio's last four years before his death in exile aged just 39, in 1610. Comparison between two versions of the 'Supper at Emmaus', just 5 years apart, showed the transformation from richness and colour to a darker, more humane vision. Caravaggio's stunning chiaroscuro and drama that inspires film-makers like Jarman and Scorsese. In 'The flagellation' of 1607, the tension between Christ's soft submission and the hatred of his scourger is painful to see.

'Saint John the Baptist' of around 1608 had a knowing, sad eroticism that shifted the focus between the saint and Caravaggio's street-boy model. In his last days Caravaggio was a hunted man. He bought his way out of prison and used membership of the Order of St John in Valetta to buy the Pope's pardon.

'Saint John the Baptist' of around 1608 had a knowing, sad eroticism that shifted the focus between the saint and Caravaggio's street-boy model. In his last days Caravaggio was a hunted man. He bought his way out of prison and used membership of the Order of St John in Valetta to buy the Pope's pardon.

Smooth perfectionism gives way to looser brushwork and less formality. The painter sometimes depicts himself as a hunted creature or as a seeker of absolution, or even (perhaps) as the dismembered head in 'David with the head of Goliath' (1606-10). After this period of intense creativity, Caravaggio died of fever, chasing after the ship that carried away many of his last works. The power and intensity of these last paintings, several of them on a huge scale that would show poorly here, stunned me. Attempts at analysis seemed superfluous. Nothing to do but drink them in.

Smooth perfectionism gives way to looser brushwork and less formality. The painter sometimes depicts himself as a hunted creature or as a seeker of absolution, or even (perhaps) as the dismembered head in 'David with the head of Goliath' (1606-10). After this period of intense creativity, Caravaggio died of fever, chasing after the ship that carried away many of his last works. The power and intensity of these last paintings, several of them on a huge scale that would show poorly here, stunned me. Attempts at analysis seemed superfluous. Nothing to do but drink them in. -

In Brighton and on a train

Just outside Brighton, on Devil's Dyke, the freckled fellow who spontaneously offered me the chance to try out his vast two-handed kite.

In the Lanes, at English's restaurant, the post-stag party that bought us all champagne and an Italian waiter called Tino who made me tea just like he did in Italy, from a teabag and mint leaves. He was all friendliness and spontaneous unprofessionalism and said he'd never made tea like that for a customer before.

On a train back from London, delayed and en route to a replacement bus, a fellow dressed as St George who offered around chocolate cookies. And a slight young Albanian with faltering English and coal-black eyes, who three times offered me his coat as I shivered on the cold bus and on the station platform.

Gratefully I took it, then put it back on his shoulders when I remembered that after all I had my cagoule. He had to be up in five hours for building work. He seemed not at all surprised that I'd thought of travelling to the land of the eagles, and said I should marry an Albanian, because they were very good. I waved and wished him all good luck and wondered if I should have done more in the cause of international relations... -

Lempicka on Dr Who

I was ludicrously pleased to spot a version of Tamara de Lempicka's unfinished portrait of Tadeusz de Lempicki featuring in Episode 6 of the new Dr Who. Her heroic, geometric style was perfectly suited to a portrait of the nasty Geocomtex boss Henry van Statten, played by Corey Johnson.

I was ludicrously pleased to spot a version of Tamara de Lempicka's unfinished portrait of Tadeusz de Lempicki featuring in Episode 6 of the new Dr Who. Her heroic, geometric style was perfectly suited to a portrait of the nasty Geocomtex boss Henry van Statten, played by Corey Johnson.

The 1928 original is in the Musée Georges Pompidou in Paris, but featured in the Royal Academy's terrific Lempicka show last year. Van Statten's look seemed to have been influenced by another striking de Lempicka portrait, of Dr Boucard, her Swiss Chemist patron. I'm almost a complete convert to Christopher Ecclestone as the Doctor, even down to his street-wise northern grittiness, though quite where the great Gallifreyan got his Manchester accent is beyond me.

The 1928 original is in the Musée Georges Pompidou in Paris, but featured in the Royal Academy's terrific Lempicka show last year. Van Statten's look seemed to have been influenced by another striking de Lempicka portrait, of Dr Boucard, her Swiss Chemist patron. I'm almost a complete convert to Christopher Ecclestone as the Doctor, even down to his street-wise northern grittiness, though quite where the great Gallifreyan got his Manchester accent is beyond me.

See http://www.goodart.org/artoftdl.htm for more on de Lempicka (1898-1980)

-

Twilight of the Gods, ENO

'What use is my wisdom against this chaos?' sings Brünnhilde in Phyllida Lloyd's production of 'Twilight of the Gods' at the Coliseum in London. After almost six hours of climactics, Wagner's Ring Cycle ends as Brünnhilde immolates herself together with the cursed ring of the nibelung which is to be purified by the same fire that will take her to her beloved Siegfried.

'What use is my wisdom against this chaos?' sings Brünnhilde in Phyllida Lloyd's production of 'Twilight of the Gods' at the Coliseum in London. After almost six hours of climactics, Wagner's Ring Cycle ends as Brünnhilde immolates herself together with the cursed ring of the nibelung which is to be purified by the same fire that will take her to her beloved Siegfried.

This was the first time I had seen more than 'the Valkyrie', the second in the cycle. That production in Budapest stunned me, every emotional nuance of the characters seemingly mirrored by the wonderful expressiveness of the orchestral writing.

The ENO production has been more controversial. I sent my sister to the much shorter 'Rheingold' - number one in the cycle - as her introduction to live opera. She and her husband loved the music and the light-hearted staging.

Traditionalists found plenty to gripe at: Wotan seem to have been partly inspired by Ozzy Osbourne and we saw him in the bath. A soap opera in every sense. On balance, I enjoyed the 'home life of the immortals' staging. The non too subtle story was that the Gods have crises just like characters in 'Eastenders'.

Even so, a measure or two tragic grandeur in the final part of the Ring seemed essential, even for the most contemporary of productions. Act one, the longest at over two hours, began with the lady norns getting their knitting of time in a twist. The Rhinemaidens pole danced again and the valkyrie were encouragingly punky (as seen at last year's Glastonbury Festival). But the singing lacked oomph, wicked Hagen was off-key and Siegried was underwhelming.

It got much better in the second and third acts. Siegfried's death and funeral march and Brünnhilde's burning were terrifically involving. The Rhine rose to cover her ashes and Valhalla fell with three vast shimmering golden curtains and a fade to black.

Powerful stuff and far too complex for me to fully comprehend after just one performance. The sensual, amoral music thrilled me but the performance lacked the devestating impact I hoped for. Am I becoming jaded or can the English not do Wagner?