‘The trouble with religions is they talk far too much about God!’ These words, spoken to the Revd Jamie within five minutes of meeting him, say a lot about mother. She disliked showiness, pretence and anything bogus. She had a very sharp mind – and it was sharp right to the end – and a knack for cutting to the truth when you least expected it.

‘The trouble with religions is they talk far too much about God!’ These words, spoken to the Revd Jamie within five minutes of meeting him, say a lot about mother. She disliked showiness, pretence and anything bogus. She had a very sharp mind – and it was sharp right to the end – and a knack for cutting to the truth when you least expected it.

She was the second eldest of five children, born to an engineer and saintly mother – who was herself one of 13, and people said took after the Queen Mum.

Doris grew up on the edge of the Fens in Peterborough surrounded by many friends and this large and loving family. I know she would be so delighted to see you here today.

We knew that we could always depend on her for quiet and sure counsel – even if it wasn’t necessarily what we wanted to hear. She shared with my father Noel a delight in providing impromptu hospitality, sometimes for slightly bemused complete strangers he brought home from Sonning.

Doris’ family moved down to Reading before the war, and her first job was working for old Mr Heelas at what became John Lewis. She loved returning to Peterborough to keep the books for her uncle Joe, who had peacocks, ran a farm and took her to watch his horses race.

Later she worked for a remarkable insurance broker called Sam Loades. It was there she met her first husband, Stan. Mr Loades was famously generous, showering the newly-married couple with regular gifts even after she was assigned to war work for the Inland Revenue. There she was asked to set up Reading’s P45 section ‘because you know as much about it as any of us’.

Doris and Stan helped her younger brother Ronald Allen realise his dream to become an actor, supporting him through RADA and seeing every production. She loved the theatre, and remembered meeting stars like Richard Burton and Vivien Leigh who she met on the set of the first Titanic film, A night to remember. Stan’s work took him to Birmingham and especially Newcastle where she delighted in the warm character of the Geordies.

Doris and Stan eventually parted and she was whisked off to Australia by Noel who she met on a Farmers’ Union holiday on the river Rhine. They were amazed to discover they had been born in the same street, and she was enthralled by his stories of sheep-shearing in the bush and dam-building in New Zealand. In Adelaide she worked on the Australian Stock Exchange where she said it was pointless speculating ‘because even the brokers never made any money’.

When they returned to England ‘because you’d better choose between Australia and me!’. She persuaded father to take a job at the flour mill in Sonning, which she remembered from her childhood trips along the river.

For Linda & I, that we were brought up by the most wonderful mother almost goes without saying; she brought these same qualities to her role as grandmother to Sarah and Katy.

She threw herself into community life, having great fun organising a fund-raising auction for the primary school. She became secretary of the Pearson Hall and helped oversee its refurbishment. She was produce show secretary, founded the Sonning Art Group and was an enthusiastic member of the village table tennis club. She loved the Burns Nights, the Elizabethan evenings at the White Hart and a famous ‘tramp supper’ where everyone dressed as vagrants.

Our mother loved the natural world. She took great pleasure in sharing what we children called her ‘kitchen sink discoveries’ – an upturned glass that moved on its own on a meniscus of water, or the sudden flash of a colourful bird seen from her belovèd kitchen window. She loved the SUMMER, and especially our three-week escapes to a beach-hut at Mudeford. There she rested from the hard work of making ends meet, whether providing bed and breakfast for four students or keeping the books – and my father – on track in the newspaper business they ran together.

Our mother loved the AUTUMN, as a time of harvest. She and a group of friends had great fun helping out with the potato picking in Sonning Eye and she made pots of jam with the soft fruit my father grew in the garden.

Our mother loved the WINTER and delighted in remembering how we children, just arrived in England, were got out of bed to watch the magical snowfall down by the river, in the light of the French Horn floodlights.

Our mother loved the SPRING most of all. She was an accomplished artist and in that season took great pleasure in going out to paint. She joked how, long ago, she had studied art and was awarded the prize for ‘the most promising student’ – because she had come on from such a very poor start.

For her, the Spring was a time for new beginnings; for the reawakening of nature after the dark of winter. So whatever we are now feeling, I know she would want us to be comforted and to look forward – just as it says in our second reading.

Doris began to succumb to debilitating illness three years ago, stoically bearing the pain and discomfort, with the regular support of so many loving friends and neighbours. She kept her ability to look on the bright side, even to the end.

The day she died, she listened at Sue Ryder – where they took the most wonderful care of her – to a choir that sung ‘Hark the Herald’. Jamie said prayers with her. Two days before she had told me – somewhat wondrously – that she’d taken communion for the first time in some 70 years.

This was a good life, a simple life, a true life, and a life of LOVE.

‘May she rest in peace and rise in glory’.

Music included 'Summertime' and 'Bist du bei mir' – translation

Listen to 'Bist du bei mir' as an MP3 sung by Elio Battaglia

The Thames at night. Dark outlines of tall trees on the bank side. It is a magical summer evening. In the moonlight, the engine of the little boat putt-putts gently, its prow pushing through a layer of eerily beautiful river mist that rests on the water, but does not obscure our view ahead. We are on our way home after a good pub dinner. On the walk back to the boat we passed

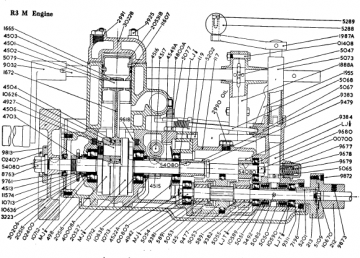

The Thames at night. Dark outlines of tall trees on the bank side. It is a magical summer evening. In the moonlight, the engine of the little boat putt-putts gently, its prow pushing through a layer of eerily beautiful river mist that rests on the water, but does not obscure our view ahead. We are on our way home after a good pub dinner. On the walk back to the boat we passed  Cuthbert always turns heads, often in admiration, but sometimes in sympathy, since the Stuart Turner has a reputation for cantankerousness. Before shelling out for a professional re-build we even attempted an engine overhaul ourselves, hand-cutting seals, and cleaning out decades of gunk, referring to the original manual with its alarmingly complex diagrams and wonderfully mysterious line 'a spare jet is always a convenience'. From being a complete novice I have been initiated into the frequently infuriating idiosyncracies of Stuart Turner engines. We have uncovered a world of specialist experts, beavering away in their intriguing workshops: engine restorers, cover cutters, tiller turners and master boat-builders for whom 20 coats of varnish is the norm.

Cuthbert always turns heads, often in admiration, but sometimes in sympathy, since the Stuart Turner has a reputation for cantankerousness. Before shelling out for a professional re-build we even attempted an engine overhaul ourselves, hand-cutting seals, and cleaning out decades of gunk, referring to the original manual with its alarmingly complex diagrams and wonderfully mysterious line 'a spare jet is always a convenience'. From being a complete novice I have been initiated into the frequently infuriating idiosyncracies of Stuart Turner engines. We have uncovered a world of specialist experts, beavering away in their intriguing workshops: engine restorers, cover cutters, tiller turners and master boat-builders for whom 20 coats of varnish is the norm.

A complete professional re-build of the entire engine, extensive work on the hull, much re-painting and re-fettling inside and out. Family picnics and late-night trystings, an epic journey to the tidal Thames, and even a wedding, when the newly married couple travelled to their reception beneath a flower-bedecked bower. A Sun-trained photographer bawled 'over here darling!' as the bride boarded. Toffs on gin-palaces toasted them in champagne and swimming boys spontaneously roared their approval.

A complete professional re-build of the entire engine, extensive work on the hull, much re-painting and re-fettling inside and out. Family picnics and late-night trystings, an epic journey to the tidal Thames, and even a wedding, when the newly married couple travelled to their reception beneath a flower-bedecked bower. A Sun-trained photographer bawled 'over here darling!' as the bride boarded. Toffs on gin-palaces toasted them in champagne and swimming boys spontaneously roared their approval.

Yesterday I took down my father's full size scythe for the first time since his death in 1990. He looked after it well, cleaning and honing the long blade, ideally shaped for cutting down the nettles at the bottom of the garden. The long wooden handle, with its two hand grips worn smooth from years of use, curves with potent elegance, making scything a kind of dance: my body twists as the blade slices, lopping the heads off the nettles as they fall to the ground. But I've never used my father's scythe before, and I haven't yet sharpened it and the blade catches on something tough in the undergrowth. He always took care never to do that. The thin, curved tip of the blade is torn and as I fiddle with it pointlessly, comes away in my hand. And in that moment I am suddenly ashamed as I hear his voice in my head: 'now that wasn't a very clever thing to do'.

Yesterday I took down my father's full size scythe for the first time since his death in 1990. He looked after it well, cleaning and honing the long blade, ideally shaped for cutting down the nettles at the bottom of the garden. The long wooden handle, with its two hand grips worn smooth from years of use, curves with potent elegance, making scything a kind of dance: my body twists as the blade slices, lopping the heads off the nettles as they fall to the ground. But I've never used my father's scythe before, and I haven't yet sharpened it and the blade catches on something tough in the undergrowth. He always took care never to do that. The thin, curved tip of the blade is torn and as I fiddle with it pointlessly, comes away in my hand. And in that moment I am suddenly ashamed as I hear his voice in my head: 'now that wasn't a very clever thing to do'.

Pleasing to find the GPO's film

Pleasing to find the GPO's film