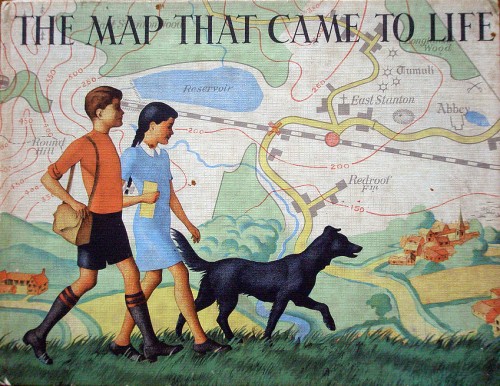

A worthwhile post on English Buildings drew my attention to Ronald Lampitt's illustrations in The map that came to life, a children's book first published by OUP in 1948. Elsewhere there's also a complete set of spreads and a page about Lampitt's map of an ideal city.

A worthwhile post on English Buildings drew my attention to Ronald Lampitt's illustrations in The map that came to life, a children's book first published by OUP in 1948. Elsewhere there's also a complete set of spreads and a page about Lampitt's map of an ideal city.

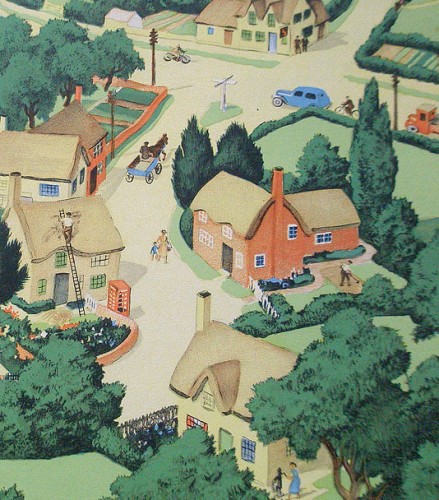

The beautifully illustrated cover is slightly reminiscent of Seurat's 'La Grande Jatte', without the pointillism. The book celebrates the fascination of maps as graphical language - ways of representing in two dimensions the richness of the real world. Lampitt paints the archetypal romantic (and very idealised) English village, set in a perfect landscape:

"These two children set off on a walk across unfamiliar country with only their map for guidance. They talk to strangers – who give them fascinating nuggets of local information rather than luring them into dark corners. Their dog spends most of its time off its lead, rivers and lakes hold no terrors for them, and, of course, this being 1948, they are not much troubled by traffic."

Lampitt also worked for Ladybird, including the 1967 title Understanding maps, but information on him is scarce. Google Earth can't compete with Lampitt's golden vision of English Never-Never-Land.

Lampitt also worked for Ladybird, including the 1967 title Understanding maps, but information on him is scarce. Google Earth can't compete with Lampitt's golden vision of English Never-Never-Land.  Secondhand copies appear rarely. A reprint is certainly overdue.

Secondhand copies appear rarely. A reprint is certainly overdue.

A special kind of Witney blanket was sold to the hugely powerful Hudson's Bay Company in Canada which traded them with native Americans for beaver furs. These

A special kind of Witney blanket was sold to the hugely powerful Hudson's Bay Company in Canada which traded them with native Americans for beaver furs. These

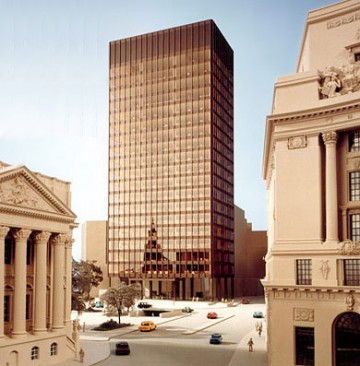

Walk into the open rotunda at the centre of the development (with its irritating Dayglo coloured window casements) and take the lift to the Conran-run 'Coq d'Argent' roof garden restaurant and a whole new impression forms.

Walk into the open rotunda at the centre of the development (with its irritating Dayglo coloured window casements) and take the lift to the Conran-run 'Coq d'Argent' roof garden restaurant and a whole new impression forms.

It's funny in a

It's funny in a

The

The

What is the 'real meaning' of art and what value should be placed on what is 'authentic' over the work of copyists?

What is the 'real meaning' of art and what value should be placed on what is 'authentic' over the work of copyists?

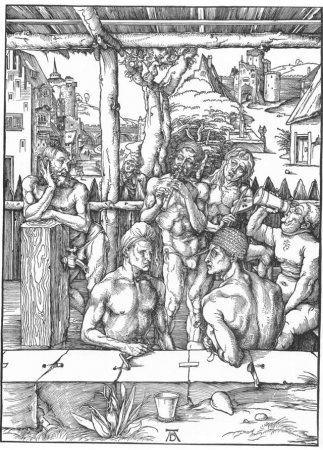

By Dürer's time the artist, not the subject, was the focus. His work – including a prominent monogram – was faithfully copied by a highly talented printmaker called Marcantonio Raimondi. In 1511 Dürer issued a devastating warning to anyone tempted to infringe what he was effectively asserting as his copyright: "Hold! You crafty ones, strangers to work, and pilferers of other men’s brains. Think not rashly to lay your thievish hands upon my works. Beware! Know you not that I have a grant from the most glorious Emperor Maximillian, that not one throughout the imperial dominion shall be allowed to print or sell fictitious imitations of these engravings? Listen! And bear in mind that if you do so, through spite or through covetousness, not only will your goods be confiscated, but your bodies also placed in mortal danger."

By Dürer's time the artist, not the subject, was the focus. His work – including a prominent monogram – was faithfully copied by a highly talented printmaker called Marcantonio Raimondi. In 1511 Dürer issued a devastating warning to anyone tempted to infringe what he was effectively asserting as his copyright: "Hold! You crafty ones, strangers to work, and pilferers of other men’s brains. Think not rashly to lay your thievish hands upon my works. Beware! Know you not that I have a grant from the most glorious Emperor Maximillian, that not one throughout the imperial dominion shall be allowed to print or sell fictitious imitations of these engravings? Listen! And bear in mind that if you do so, through spite or through covetousness, not only will your goods be confiscated, but your bodies also placed in mortal danger."

According to some '

According to some '

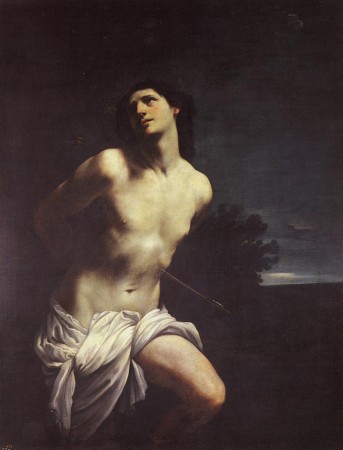

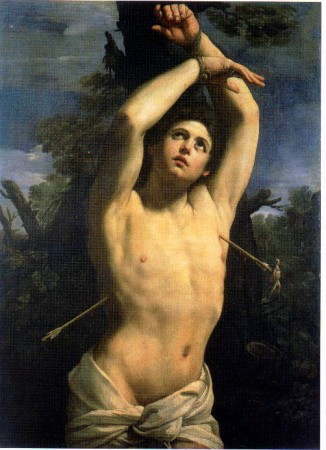

Seven paintings, all of the same subject: a beautiful, almost naked youth, tied to a tree, in the throes of martyrdom. Five are almost identical versions of the same composition, from galleries as far away as Puerto Rico and New Zealand. All are uncompromising in their directness. The painting from Genoa inspired Wilde, Mishima and Pierre & Gilles. Stendahl claimed they so distracted the faithful that they had to be removed from churches.

Seven paintings, all of the same subject: a beautiful, almost naked youth, tied to a tree, in the throes of martyrdom. Five are almost identical versions of the same composition, from galleries as far away as Puerto Rico and New Zealand. All are uncompromising in their directness. The painting from Genoa inspired Wilde, Mishima and Pierre & Gilles. Stendahl claimed they so distracted the faithful that they had to be removed from churches.